We all remember how beautiful that morning was. Azure sky, Indian summer, almost too perfect. For me, it was also eerily quiet. I was editor of an upstate New York newspaper, and had just arrived in the office. Quiet, spacious, comfortable—everything that New York was not. New York is crowded and uncomfortable and hard, and even though I loved my job, I was already longing to go back.

One of my writers was just coming into the office. It was his birthday. At 8:30 that morning, September 11 was a perfectly good day to be born on.

I got a phone call. It was a writer from our other office. “Are you watching TV?”

“No … why?”

“A plane hit the World Trade Center.”

I’m a history buff. My first thought is the B-25 bomber that crashed into the Empire State Building in 1945. A terrible accident.

There is a pause on the phone. “My God—another plane hit.”

No accident. War.

The day is a blur. TV news had long ago killed almost all afternoon edition daily newspapers, but not ours. This meant that we were one of the very few newspapers in the country that hadn’t gone to press yet. Calls into the city couldn’t connect, and any national news Web site was down under tremendous strain, but I had direct access to the AP wire. Only two years before, I’d written a 12,000-source thesis on how terrible instant news is during a crisis, but now I was living it and breathlessly shouted each new AP report to the newsroom, with no way of knowing what was true. The Pentagon had been hit? A car bomb went off at the State Department? A fighter jet shot down an airliner?

I was interviewing, designing, and in-between trying to call or instant message friends to see which ones were still alive. It took three days for all of them to be accounted for—three days where I slept a couple hours at most. The image at right was our front page, on the streets by 11 a.m., with whatever we could verify. Like so many photographers, I am at heart a crazy person, and my impulse was to run right toward the danger. But I was far away, and had to hold the paper together, so I sent a writer.

Standing on the Twin Towers was a dizzying experience. I’d been in the Sears Tower and CN Tower, which are taller, but the Twin towers had a couple things that made the experience breathtaking. First, the city sprawled out before you was New York, and all of it, given the towers’ location. But what blew your mind was that you were so far up in the sky, placing the entire city into a tiny perspective…and there was another tower right there.

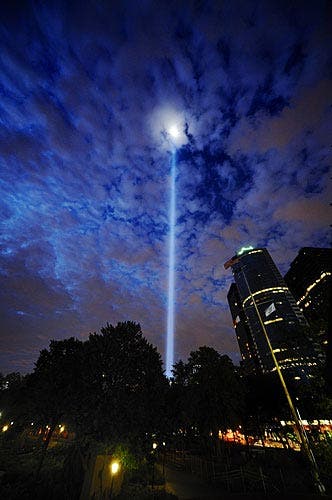

More than anything our memories of the events a decade ago show the power of pictures to burn memories into our mind. Whether at the hands of brave photographers or news broadcasters, we remember the explosions, the people jumping, the horror. Think about this—why are the Twin Towers the overwhelming symbol of the day, taking almost all of the attention, when the Pentagon was also attacked? Because the towers lived in the heart of where we make our stories and pictures, and the Pentagon is necessarily shrouded in secrecy. Without the pictures, the cross of iron girders, the explosions, the rubble—everything is indistinct. It is the photographers who take our experiences and lock them in amber, who give perspective.

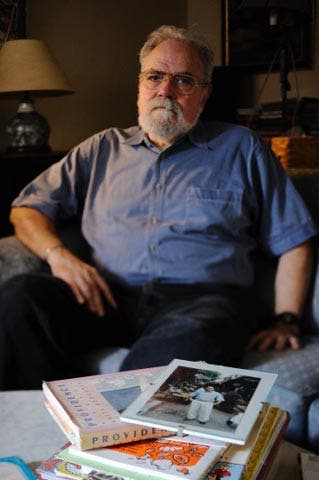

One of the things I love about photography is that there is always something different around each corner, but that also means there are new challenges, and the biggest ones are not technical. I recently was given an assignment to photograph a couple whose son had been killed on 9/11, with a picture of their son. I could barely begin to fathom the emotional response this could bring for them, so I kept myself as empathetic and open as possible.

Luckily, they were incredibly gracious and had been through many media requests before. In the picture above I used a tilt-shift so that both he and the photo could be in focus without him just holding it up for the camera. It didn’t follow any sort of hard news rules, but I didn’t want to have to rearrange their house for the photos, so I was glad for the serendipity that the book on the top of their pile was “Providence.”

Though they had all of the sadness and anger any parent would go through, the couple’s message is about forgiveness. It’s controversial because it’s hard to even understand where to start. Forgiveness for me has always been tied to repentance, and the nature of this self-destructive crime makes repentance impossible. But without it, violence becomes an unstoppable chain, a force that sweeps up all up alongside it.

I hope we can. I believe that you can’t be a truly good photographer of people unless you love people, both in general in all of their chaos and uniqueness and variation, and in a specific connection that comes through your viewfinder, of where people are coming and going from before and after the moment, and what is within them during. We can be stupid and crazy and small, but we can also do so much with our lives, and it would be awfully nice if we stopped killing each other quite so much.

I could have wrapped up the assignment in two minutes of photography, but I wanted to press on. There is more to life, even after tragedy, and I wanted to give context to the story, so I brought them together to live out some simple moments of their daily life. It brought out things in them that you can’t see when you’re holding a picture, reminding us to live even as we remember what we have lost.

Back to now, 10 years later. After years on hold, One World Trade Center is racing to the sky at almost a floor per week. There isn’t a single aspect about 9/11 that isn’t controversial, especially questions of where we go from here and how we rebuild ourselves as a city and country, but all I know is that I’m glad to be back. I’m in the thick of New York again, and I can see One WTC from my studio window. I’m in a city that never sleeps because we are too busy working and playing and living life, not because of fear, and I can’t imagine leaving.