Q: You’ve had access to incredibly charismatic people who lived their lives in the public eye – everyone from presidents to rock stars. What do you think your photography revealed about some of these people that couldn’t otherwise be seen in their everyday public lives on the global stage? What separates or distinguishes you, the photographer, from the spectator?

A: The real images only come once the subject forgets about your presence and you’re just part of the scene in their world.

It’s all based on trust between you and the subject. I was watching a “60 Minutes” segment on the very talented photographer Danny Clinch, who is trusted by many musicians to get places where others cannot – like the trust I had with politicians.

To shoot these inside “behind the scenes” jobs you need to blend into the room. I use quiet cameras without flash and not much gear. Less gear equals more pictures in my thinking. You’re not burdened by all that stuff.

You also have to dress the part – coat and tie, always, unless it’s a “casual day” and you can take the tie off. Be the human chameleon.

I can’t stress how important how you look is when you work. People who don’t know you judge you by what you have on that particular day. As shallow as it might be, it’s all we have to go by usually when we meet anyone. At least Danny Clinch gets to dress hipper than I did on the job.

Q: How does one transition from the sex, drugs and rock and roll scene of the 70s to photographing presidents? (Anecdotes welcome.)

A: Being on the campaign is like a long rock tour. Being with Bill Clinton in 1992 was a combo of Elvis and The Stones, especially in the last two months.

You’re traveling with this core group every day and night. You know them better than your spouse at times. Then, in time, there’s more people on the tour and never-ending flights, cities, hotels, hangers-on, etc. I saw a big shift in campaign health habits from 1983 to 2001. There was more smoking and drinking in 1983, and slowly it all declined. I think the press got older and smoking got banned everywhere. Drugs were never really in the mix, and no one had time or energy for sex.

I always liked the question from the public standing near the front area, “What TV station do you work for?” I’m carrying two still cameras, “What?”

Q: How does personal political bias come into play as political photographer? Are there any tense or difficult images you captured that forced you to examine or reconcile your personal biases with what you were trying to convey on film?

A: I leave personal political views at home. I view myself as a recorder of history, nothing more. Everyone gets the same professional treatment and coverage. I didn’t vote for the longest time when I was doing behind the scenes work, since I didn’t want to have any dog in the fight. I’m often asked “How could you ever work with Name Your Own Hated Politician Here – it was funny. As a photojournalist it never made any difference to me. I would hear it from all parties. The politicians I photographed treated me very nicely. I’m still in touch with many of my subjects.

Q: You also produce, shoot and edit films, including the documentary “Our Molokai,” which effectively protested the construction of approximately eighty 490-foot industrial wind turbines in Oahu. Your editorial/corporate photography also features Hawaii in the forefront. When did you move to Hawaii and how has it changed the tone of your work and your vision?

A: I grew up on Oahu and now live on Molokai across the channel. Oahu is the Commerce Island and Molokai is very rural – a 20-minute flight away. That turbine situation was interesting, to say the least. Of all the people in the world to piss off with the plan of 50 to 80 490-foot wind turbines in front of their house – it was me! The state’s idea was to ruin the west end of Molokai to help power to Oahu. It would have been a disaster both environmentally and fiscally. A grassroots group was formed called I Aloha Molokai. I made some short films and sent them to the governor, all state politicians, and had a public following on YouTube.

“Our Molokai” was the last film we did and that was deal ender. After it was released, the landowner on Molokai did not renew the lease to the energy company and the idea died. No state politician wanted to fight an ugly fight against an island trying to keep its rural country values and Hawaiian culture.

Q: Who are some contemporary photographers whose work you admire and respect?

A: The late Eddie Adams had a big influence on my photography when I lived in New York in the early 1980’s. He really made me work harder to create the best images I could. Eddie told me after first reviewing my portfolio in our first meeting, “Your pictures suck until I tell you otherwise.” Man, if you could please Eddie, you knew it was a great shot. I remember helping to build the early stages of The Barn (which is where the Eddie Adams Workshop is now held) with photogs Jim Wilson, Ed Hille, Ron Frehm and John Filo. I have zero construction skills, but could carry stuff and shoot photos which are in my archives. Hanging out with Eddie up at the farm was a priceless experience for all of us.

Neil Leifer gave me my first job in NY in 1979 being one of his assistants. Those old time black line Speedotron packs were not lightweight. That got me in the door at TIME.

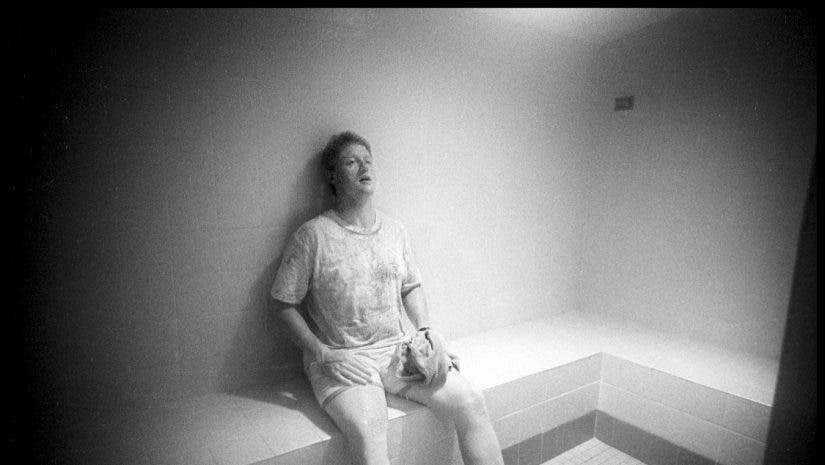

Neil and I are still in touch. I was honored a few years ago when he asked me if I wanted to do a print trade – he got Clinton in the steam room, I got his classic Ali standing over Liston. I think I got the better end of that deal.

And, of course, I love the work of very talented Robert Caplin because he got me this interview with Adorama.