Look at all the film you save by shooting two images on one frame! Just kidding.

The reason for making multiple exposures is to create powerful images, not to save film–or space on your memory card. Making multiple exposures where I talked about photographing your subjects in front of a black background, and composing so the images would not overlap (which I explain elsewhere), is relatively easy. Now let’s take it to the n level: Toss out that dark background, and let the images overlap.

With two overlapped images, something quite different now happens. Instead of each image appearing separate and distinct, the images merge into each other. This can be a very good thing. It opens a host of creative possibilities– flowers can glow, ghosts can sneak around in your living room, your world can look like an impressionistic painting, black shadows can become suffused with vibrant or subtle color. Of course, your camera must be capable of making double exposures. But don’t stop reading if your camera can’t. You can create these effects in Photoshop, and I’ll describe the Photoshop way with each example.

Control exposure? It’s simple math

The key to doing it right is controlling the exposure. When you expose two images on the same frame of film, the film (or the image sensor in your digital camera) will receive a double blast of light. The result: overexposure. And if you make three, four, or twenty-four exposures on a single frame, you can guess what will happen. So you must make the appropriate exposure compensations. Fear not, it’s actually quite simple.

Let’s begin with double exposures and leave making multiple exposures (that is, more than two images on one frame) for another article. The basic rule for double exposures: You need to underexpose each picture by one stop. That puts half as much light onto the film (or digital sensor) with each shot, and the combination of the two will add up to the desired overall exposure.

You can adjust the exposure by putting the camera in manual-exposure mode, taking your meter reading, then either changing the shutter speed so it’s one step faster, or closing the aperture down one stop. For example, if your meter suggests f/8 at 1/125 sec, then use either f/8 at 1/250 sec or f/11 at 1/125 sec. Another way to do it is to use the exposure-compensation button/dial. Simply set it to one-stop underexposure– that’s the “minus” setting. Just don’t forget to move it back to zero when you’re through, or your n pictures will not make you happy.

How white affects overlapping color: There’s one other thing you need to know about. That is that white and very light areas will “burn through” darker areas. Suppose you have two subjects, such as the red leaves in the picture on the left and the white flowers in the picture in the middle. Make a double exposure of the two, and the result will be like the picture on the right– the petals of the white flowers show through the darker colors in the other image.

So what great effects can you make with two overlapping images? Well, you could do something like in the above illustration, superimposing two very different subjects. Just make sure to plan before you shoot, keeping in mind what will happen to the tones when the two images are combined.

In Photoshop: The basic double-exposure effect is really simple to achieve in the computer. You can have lots of fun trying all sorts of combinations, and choosing the most effective ones. Open two images. Important: they must be the same resolution and format. On one picture– it doesn’t matter which one– Select > All> Copy. Then paste this picture onto the other one (Edit> Paste). Then, on the Layers palette, change the Blend Mode to Lighten. It’s the Lighten mode that produces the magic. It may seem logical to change the opacity, but don’t do it. Changing the opacity will just mute all the colors and may make the image look kind of muddy.

Two focal lengths

Another creative approach to double exposures is to take two shots of similar subjects, making one a wide-angle, the other a close-up. In the above composite, I used a very wide-angle lens for the field of tulips plus a close-up of one of the flowers. I think flowers are good subjects for multiple exposures, so I tend shoot lots of them, but you could shoot a parking lot full of cars, a room full of shoes, a platter full of fruit, or whatever else appeals to you.

The Photoshop method is the same as described in the first example: Cut, paste, lighten.

Zoom plus sharp

Zooming the lens during a longish exposure changes a busy scene into a burst of lines radiating from the center of the picture. Find a very busy subject with lots of color and tonal variations, put the camera on a tripod, and zoom the lens while making a long exposure of about one second. For the second exposure, find a light-colored subject. Forget the “rule of thirds” and compose it so it’s in the center of the frame.

In Photoshop: Open a busy scene and a close-up. Resize the close-up so it will fit neatly into the middle of the picture. Create the zoom effect on the busy scene by clicking Filter> Blur > Radial Blur > Zoom. Play with the amount until you see streaks you like. An added advantage of doing it in the computer is that you can place the center of the radiating lines anyplace you want– just use the Move tool and drag the center dot on the diagram to wherever you want it. Then use the basic Copy/Paste/Lighten steps to add the close-up to the zoom image.

Glow Flowers

I call this the glow-flower effect because it makes the flowers in my pictures seem to glow. Other people call it a halo effect, but whatever you call it, the effect is “loverly.” You have to use a tripod because both shots coincide exactly. Make the first exposure with the subject in sharp focus. Then, without moving the camera, adjust the focus toward infinity; this will blur and enlarge the image. Make the second exposure. Note that the amount of blur depends on how far out of focus you make the second image. Experimentation and practice will make you an expert.

In Photoshop: To produce the halo effect, the blurred image has to be larger than the sharp image, so you’ll have to do a few additional steps beyond the usual copy and paste. First, give yourself a bit of working space by using the Move tool to pull the edges of the picture outward. This doesn’t enlarge the picture– that’s the n step. Duplicate the background by clicking Layer> Duplicate Layer. On the duplicate layer, Select > All, Then go to Edit> Free Transform. You’ll see little squares at each corner of the selection outline. Use the Move tool to pull one of the corner squares out on a diagonal, but do so while you’re holding down the Alt key. Holding the Alt key insures that the image will enlarge equally on all sides and stay in the same place relative to the original image. Hit Enter.

While you’re still working on the new layer, go to Filter> Blur> Gaussian Blur. Give the blur a Radius of about 200. Then lower the Opacity to about 80 percent. You’ll see the halo and a somewhat diffuse main image. This will look quite nice, but you may want to sharpen the main image by carefully painting it with the Eraser tool.

Or, for best control when sharpening the main image, add a Layer Mask to the blurred layer. Click the icon with a little circle that’s on the bottom of the Layers Palette. Make sure the color swatches on the toolbar show black as the foreground color. Paint with black to restore the areas that you want to be sharp. If you sharpen too large an area, you can correct the problem by making the foreground color swatch white and painting out the mistake. Being able to correct a mistake is the enormous advantage of using a Layer Mask instead of the Eraser.

Ghost in the parlor

There are several in-camera ways you can get ghosts to haunt your house. One isn’t even a double exposure, but I thought I’d tell you about it anyway so you don’t feel left out if your camera doesn’t have multiple-exposure capability. I’ll start with that one. Whatever method you choose, the ghost should not wear white or very light-colored clothes; otherwise the room will not show through him or her.

1. Long Exposure. You’ll be making a ten-second exposure, so you’ll need to work in a dimly lit room and to use slow film or low ISO setting on a digital camera. Put your camera on tripod. Pose your “ghost” and have him or her hold very still. Start your exposure. After five seconds tell your ghost to move quickly out of the frame. During such a long exposure, your subject’s movement will not register on the film or sensor, but the static pose will.

2. Double Exposure, One Location. Put your camera on a tripod and be very sure it doesn’t move even a smidgen between your two exposures. Take two shots, one of the room, graveyard, or other location with the ghost, the other shot without him or her.

3. Double Exposure, Dark and Light Locations. This is easier than method two because you can handhold both shots. Have your subject stand in front of a black background for one shot, and make the other exposure of the room to be haunted. You might want to get eerier by draping your subject in black so just his head or hands show. As you know, black areas will not record on the film or digital sensor, so your exposure technique will be different with this method. When photographing the room, use the exposure recommended by your meter. The ghost, though, should be underexposed by one-and-a-half to two stops.

In Photoshop. Use your preferred selection tool to select the subject, then copy and paste him or her onto the background picture. To adjust the ghost’s transparency, reduce the layer opacity instead of changing the Mode to Lighten. An opacity in the neighborhood of 65 percent will be about right. Boo!

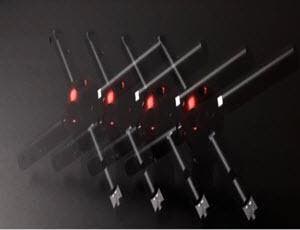

Color Flashing

No, this is not an X-rated technique– it’s a way to turn shadows and dark silhouettes into color without affecting the light areas of the photograph. The deeper the tones in the scene are, the deeper the resultant color will be.The effect is exactly the opposite of what you’d get by putting a color filter over the lens– filters produce color in light areas; color flashing adds color to dark areas.

Here’s how you do it. You don’t have to underexpose each shot as you learned in the first few techniques. Instead, meter your subject normally and make your first exposure. To prepare for the second exposure, you must meter manually. Fill the viewfinder with a sheet of colored paper. Place an 18 percent gray card on top of the paper, take your meter reading from it, remove the gray card and take the second exposure of the colored paper. If you expose according to the metered reading, you’ll turn shadows and black silhouettes into color ones. If you expose less than the meter reading, you’ll add a hint of color. In other words, the less the exposure to the color source, the lighter the resultant color will be in your picture. Adding a color exposure also reduces the contrast a bit.

In Photoshop: Open your image and create a new layer. Fill this layer with any color you like. Change the Mode to Lighten and play with the Opacity until you get the effect you like. In my examples, the opacity was 60 percent on the orange version, 50 percent on the green.