Recently, I found myself at the rather expansive Hudson Studios with a camera in tow and an eye (and attentive ear) observing/listening to the eager buzz surrounding me. The event space was playing host to a “Jazz Loft Party,” an evening of fundraising, photography, film clips and live performance organized to support the Jazz Foundation of America. “JFA” for short, it has existed for over two decades with one mission in mind: to help financially support, even find performance opportunities for veteran jazz and blues artists. It is a very worthy cause indeed. For various reasons, retirement does not come easy for those talented performers who have given their lives for so little in return.

America has provided much to the world culturally. Most notably when it comes to the progression of rock n’ roll and pop music. And the trajectory of this development can be traced to the beginnings of jazz and, specifically, rhythm and blues. JFA recognizes the importance of keeping that heritage alive by archiving the memories of those who are old enough to have been around during the scene’s latent phases but are also elderly enough to be gone from this world too soon. Leading the charge is photographer Richard Corman, a man who found himself moved by the organization’s goals. Richard volunteered to develop a project collecting the anecdotes of those who lived on the front lines. Aiding in this endeavor is camera retailer Adorama who has donated the necessary equipment used to record this effort through video and photography.

Richard is no stranger when it comes to capturing musical talent on film. He rather famously photographed a then unknown Madonna just before the release of her first hit album. Although those photographs now appear in a book titled “Madonna NYC 83,” Richard’s career should not be regulated to just that bit of infamy alone. He was an apprentice to the great Richard Avedon, an experience that opened up a lot of doors for him. I sat down with Richard to discuss his career and his involvement with the JFA.

As we chatted over coffee in a café somewhere in the Flatiron District in New York City, Richard reminisced, “my goal as a young man was not to become an artist or a photographer. I grew up in a home where my mother was a producer and my father was a doctor. So I had a creative side and I had a very academic side. So my tract was academics. I was probably going to go into Psychology, maybe Art History.” He continues, “after college I took a year off. I got to the point where photography found me.” Richard talked about how he immersed himself into his art, recalling memories of early morning shoots in the meat packing district while still a young man.

“Fast forward, I landed a job with Richard Avedon Studios and that changed my life forever. That was my PHD in photography.”

Wait a second, I thought. How does one just “land a job” with Richard Avedon without any formal training in photography? Corman answered, “Back then it was about an apprenticeship. In many ways, they would’ve liked a foundation but they wanted a blank canvas. I assisted a few photographers… it was a nightmare. It was a disaster. I went to meet with a still life photographer: ‘you’re not right for us. You’re interested in people.’ Their studio manager just went over to Avedon, they said they were looking for somebody. I call up. I go over to meet with him. Dick (Avedon) interviewed me as he was shaving before he was going out to the theater. He hired me on the spot.” Richard Corman couldn’t have asked for a better mentor. “I could have stayed a lifetime and learned something new every day.”

Richard moved on to an illustrious career. Thanks to his mother Cis Corman – who was both a producer and casting director and is known for her work on “Raging Bull,” “The Deer Hunter,” and “Prince of Tides,” among others – Richard found himself in the envious position photographing up and coming talent, not least of all is the now iconic Madonna. “My mom would call me and say ‘I met this actor or actress. You should call them and photograph them.’ And that’s how I met Madonna. I didn’t release (the photographs) for years because I didn’t think they were relevant. Not that she wasn’t relevant. It just became more relevant today. So a couple of years ago I had a show at MILK Gallery, I published a book and it just blew up.”

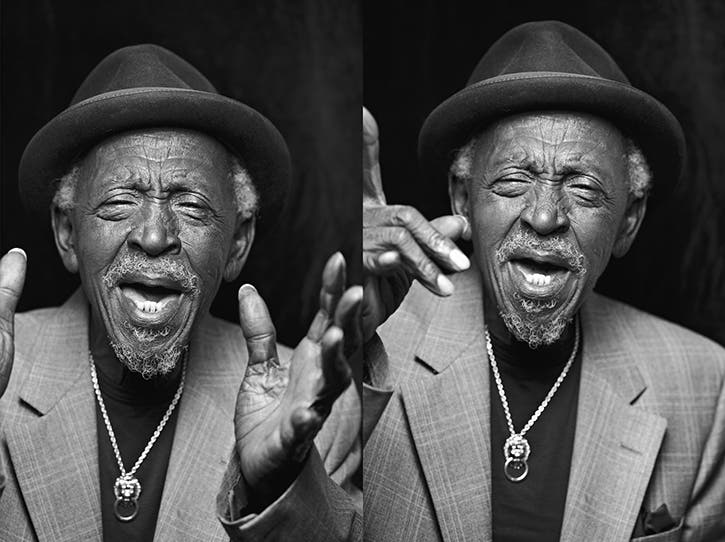

Richard has focused his lens on an array of topics including celebrities, covering the Special Olympics for over 20 years and a lot of fundraising and not-for-profit work. His ability to capture the humanity of his subjects is evident in the images displayed upon entering the Jazz Loft Party. “It began a couple of years ago,” he explains. “I was invited to a memorial for Little Jimmy Scott at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. A friend of mine was going to sing in his honor. I was blown away by the celebration of this guy’s passing. Which is what they do in the jazz and blues community anyway. But I also recognized a face there who I hadn’t seen in years, spoke to her, and was so moved and she told me she was involved with the organization and I said ‘I need to be a part of this.’”

I asked him if he is a jazz fan. Amusingly he responded, “no. I mean I am but I’m not. I mean I love jazz and blues… of course, I understand where it came from, I understand why the Stones are the way they are today. I’m not a connoisseur but I love it. At that point, I said, ‘we really need to archive and document these faces and the stories behind these legends.’”

Richard then met with Wendy Oxenhorn, the Executive Director of the JFA, a person he admires greatly. “She’s a visionary. A genius. She was a recipient of the National Endowment of the Arts grant.” Soon after he found himself in Harlem and New Orleans, finally making the project happen. “We needed to do it on the fly and some of it that you saw at the opening—“ I remarked on how it was a pretty impressive opening, especially the gallery of imagery that greeted attendees before they entered the party. Richard agreed, “what I wanted to do… They had never done something like this before… This was really the first project I’ve done with them. I wanted people to walk in and kind of… I wouldn’t say I wanted to take their breath away. I just wanted them to take a deep breath. Because I wanted them to feel it before they walked down that hallway and listen to it because it was to my mind breath taking. That was a great evening of entertainment.”

Indeed, it was. The evening itself represented an eclectic collection of blues and jazz greats. Featuring performances by The Preservation Hall Jazz Band, The Cookers, Carlos Alomar & Robin Clark of the David Bowie Band, jazz prodigy Matthew Whittaker, the legendary Sweet Georgia Brown (formerly homeless, Brown was living in Penn Station with her granddaughter before she was rescued by the JFA), Afro-Latino percussion pioneer Candido, plus many more. Performances continued well into the night from room to room and hall to hall. And the turn out was pretty incredible. One could brush shoulders with T Bone Burnett or, as was in my case, be pulled out of a room to photograph Fox Business Network’s Maria Bartiromo.

But the evening truly belonged to the jazz and blues greats who graced Hudson Studios with their presence. Footage from Richard’s documentary was projected on a screen one side of a hall while his portraits were displayed on the other. I asked Richard if there is a difference between the jazz communities from state to state. “Probably,” he said. “But they’re all fading. They’re getting older. They need to be supported and taken care of. And they want to perform because that’s their life blood. You saw Candida play the congas, I mean, he’s in a wheel chair but then he hears the music and all you see is him and his taped fingers playing the congas. And he’s 28 years old again. Or Randy Weston playing the piano at 90… this organization not only gives them an audience but supports them so they’re not begging for money.”

Richard also elaborated on Adorama’s involvement, “Adorama is an incredible collaborator. I made a presentation to them and they said ‘we’re in. This is fantastic. What do you need?’ They also sponsored the exhibition in that gallery.”

In terms of making the transition from photography to video, Richard acknowledges, “I’m learning more about the world of motion and I find it exciting. I think the directing part is the easy part. I’m comfortable with that. The hardest part is post because that’s where it all comes together.” Richard hopes to collect everything he’s shot into a collective whole. A feature-length documentary, perhaps? “Sure. If we feel it’s viable. When we edit it I want it to feel like jazz. I want it to move quickly and slowly. I hope that in some ways the film will pick up that pace.”

Please check out Richard Corman’s work at his website here. For additional information on the Jazz Foundation of America, check out their website here.