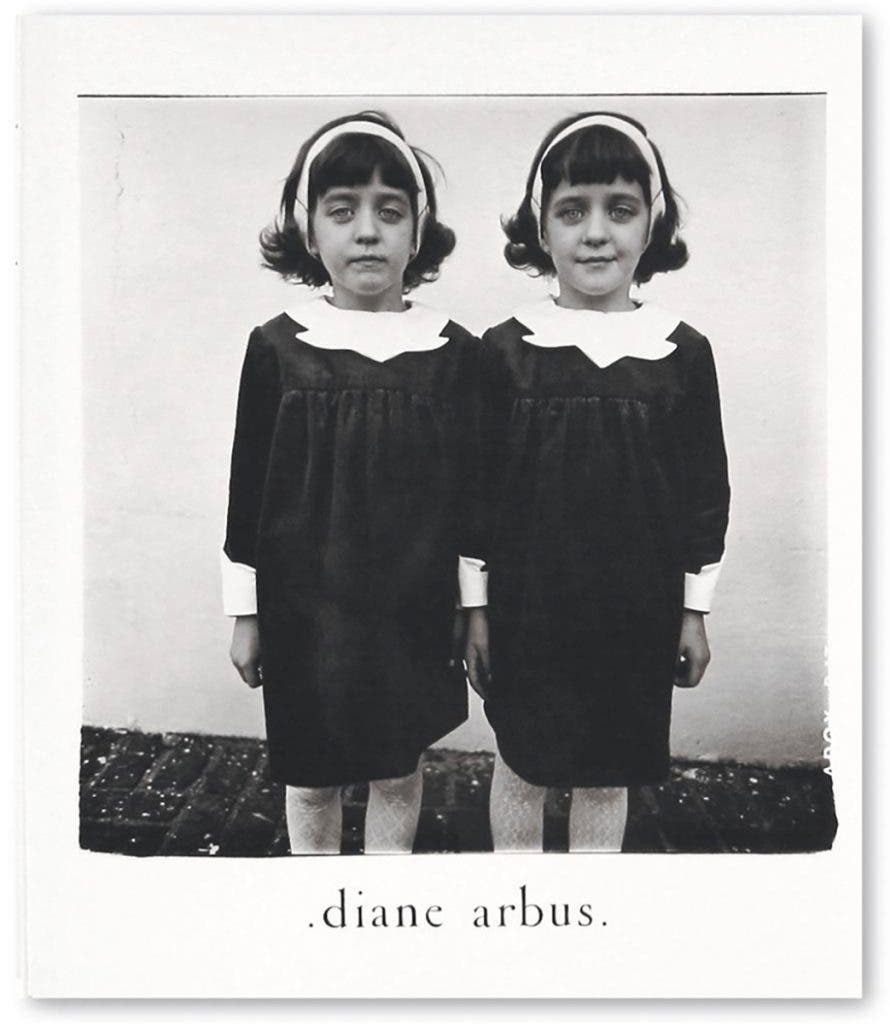

I’ve known of, and imagined stepping into the world of, Diane Arbus for almost as long as I have been a photographer. Presented as an icon, I didn’t argue as I slowly turned the pages of her posthumous 1972 monograph. Practically every picture was a dark mystery, almost unnerving, and I’m hardly the first to say it. But “mystery” still sums her up like no other single word.

The Mystery of Arbus

With mystery comes an inherent jousting between extremes. You know what you don’t know. That ambiguity has kept me returning to her, drawn in and (often jarringly) repelled in equal measure. As I discover new images or bits of biography, nothing ever registers as definitive. Even old texts I once devoured hit differently on the second, third, fourth read.

I watched A Slideshow and Talk three times before I could stop wincing and really listen to her. Recorded just one year shy of her suicide to a room full of students, her voice was shrill and manic at times. But if you could get past her pain, she had gorgeously simple truths about photography waiting for you.

When I first encountered her 35mm photograph “Windblown Headline on a Dark Pavement, NYC, 1956” at the Met Breuer’s diane arbus: in the beginning exhibition, it was like falling in love with a stranger. A mostly black gelatin-silver image of a newspaper swept up in the gritty city wind, its acquiescent abandonment entranced me. I would have followed it anywhere.

Diane Arbus: Constellation at the Park Avenue Armory

Walking into Constellation—the largest Diane Arbus exhibition ever staged in New York, now on view at the Park Avenue Armory through August 17, 2025—I experienced that same push and pull. At the exhibition’s entrance, a projection of her subjects’ eyes played, and, testing myself, I knew instantly who each pair belonged to.

But moving into the massive drill hall, the familiar Arbus tension insinuated itself again. Her images of developmentally disabled individuals, which I had long sidestepped, kept resurfacing. Scattered rather than clustered, they appeared again and again like persistent questions, black holes—dead stars—comprising no light, no counterpull, nothing but vacuous space. What did they offer us? What did the expressions look like behind her subjects’ Halloween masks? Did they know anything about cameras, and what did they think about Arbus herself? The questions were so relentless and unanswerable, I turned my back on her, ultimately judging her impulse to photograph the unphotographable.

That was my strongest takeaway from Constellation: a low note. A moment of recoil.

Moving Forward

But as Rainer Maria Rilke writes in his poem “Moving Forward,” it was like “standing on fishes.” With Arbus, I never stay in one place too long. Just enough to undo what came before.

While revisiting material for this piece, I started thumbing through my well-worn copy of Diane Arbus: A Chronology. A compilation of her correspondence, personal notebooks, and other unpublished writings, I had dog-eared so many pages. None of them seemed like a place to begin. But there was one lone, yellow sticky note I had placed on page 85, and turning to it—call it serendipity, coincidence, divine grace, or just the way it goes with Arbus and me—were excerpts of a letter she wrote in 1969 to her ex-husband Allan Arbus, reflecting on these very photographs:

“. . . I took the most terrific pictures,” Arbus writes, “the ones at Halloween in NJ of the retarded women. Somehow, and I don’t understand it at all, I mean I don’t know if the strobe didn’t fire or did, or if it was just like a fill in, but they are very blurred and variable, but some are gorgeous. FINALLY what I’ve been searching for. . . . (Doon says they look like if you blew on them they’d disappear. Like made of smoke. And Amy likes the retarded photos more than anything I’ve ever done.) . . . They are so lyric and tender and pretty . . . ”

A Secret About a Secret

And just then, as if on cue, one of her most resonant quotes echoed in my mind: “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.”

In other words, the longer you look at a photograph, the more you make it yours, and the less it can be the photographer’s. We come to understand an image based on the personal associations, opinions, and experiences that its visual elements trigger in us. And that definition necessarily propels us farther away from the photograph that the photographer believed she created.

A Photograph Is a Mirror

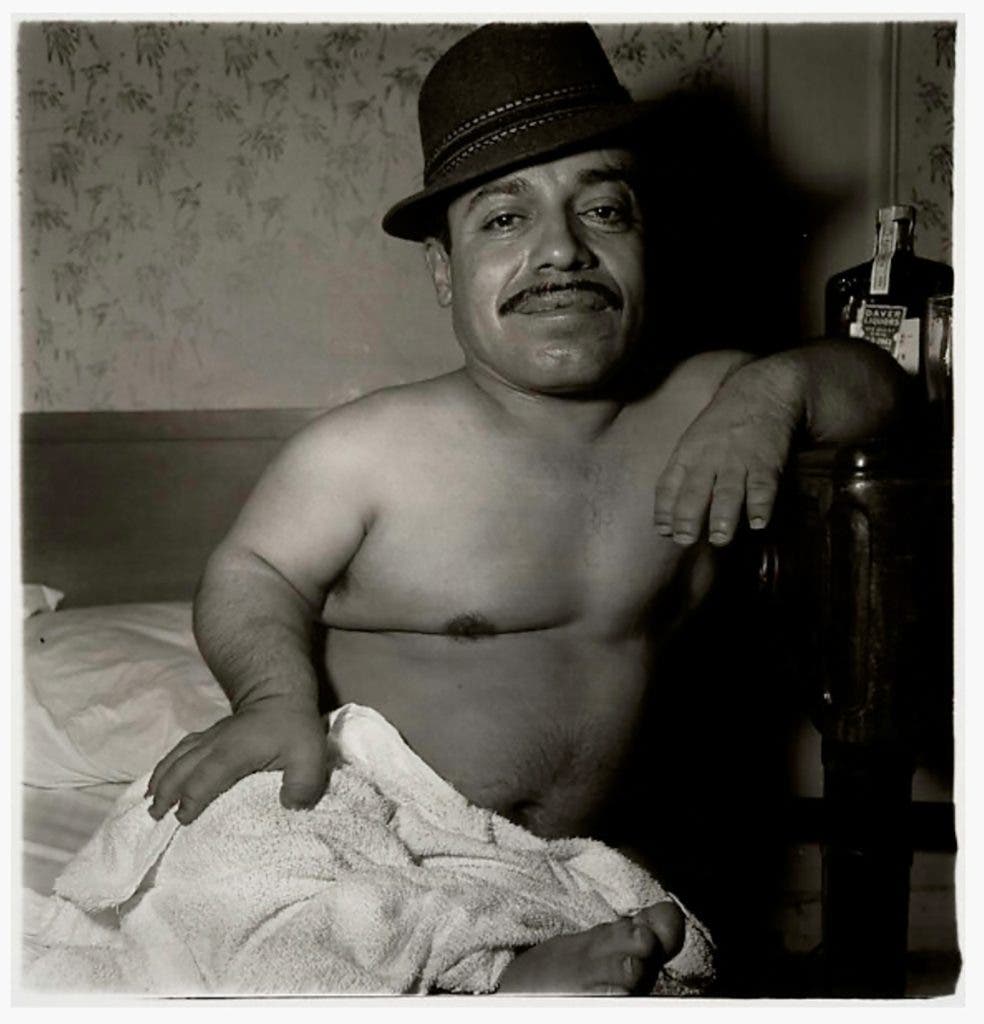

A picture of a desert landscape can evoke the awe and fecundity of nature in one person, but that same desert landscape can look barren and isolating to another. Show people her picture “Mexican Dwarf in His Hotel Room in NYC,” wearing nothing but a small towel draped over his lap, and the takeaway is even more divergent, complex, charged, and misdirected.

But it’s still the same dynamic. A photograph is a mirror. It is always a mirror. And it cannot exist without your reflection. It tells you about yourself, your emotions, your beliefs, your experiences, lines you will and won’t cross, and whatever else you are willing to hear.

And therein lies Arbus’s gift and her cross to bear.

On the one hand, she makes us feel: an attribute of all successful art. On the other hand, we might not always like the feeling. What’s more, the world we live in now is vastly different than the world that existed when she photographed. So when we extract meaning from her portraits and her impulse to photograph, we move farther and farther away from her, rendering her secret less and less audible.

Photos that Provoke

Diane Arbus’s photographs provoke us. They pull something out of us. They force us to take a stand on who we are, at the moment, as an individual and as a society. And having that mirror held up to us is what keeps us honest, grounded, and informed about ourselves and our time. This self-awareness, which her photographs have continued to manifest in us over so many decades, is precisely the role that art is meant to play.

Arbus’s images function as a necessary counterpoint, knocking us to the other side, where we stay until, like the newspaper, another gust of wind moves us elsewhere. To appreciate Diane Arbus is to be okay with not really knowing anything for long . . . above all about her.

But more than fifty years after her death, we still try.

Diane Arbus: Constellation

Park Avenue Armory, New York City

On view through August 17, 2025

Visit parkavenuearmory.org for ticketing information

Diane Arbus (1923—1971) began as a commercial photographer, collaborating with her then husband, Allan Arbus, with whom she had two daughters, Doon and Amy Arbus. She studied photography with Berenice Abbott and Lisette Model, the latter of whom encouraged her to develop her singular voice in fine art photography.

In 1967, Diane Arbus was thrust into the public eye when her work was included in MoMA’s landmark exhibition New Documents. Curated by John Szarkowski, the show presented Arbus’s photographs alongside those of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. Together, they represented a new generation of imagemakers pursuing more personal, introspective aims—departing from the socially conscious photography dominant at the time.

Although Arbus is best known for portraying people living on the margins of society, her archive is actually much more diverse than that. Her photographs continue to challenge, mystify, and inspire. She died by suicide in 1971 in New York City.

Feature Image: Tod Papageorge, Diane Arbus, 1967